-

“…Gde Djurdjev hodit, tam vam polje rodit…”

-

“…Where Djurdjev walks, there your field gives birth…” –Old South Slavic folk song

While much of the Pagan world in Western Europe and North America–from London to Lexington, Kentucky–celebrates the well-known Celtic festival of Beltane, the “fire of the god Bel,” this first of May (which is Lei Day in Hawaii, incidentally; I wish a very happy Lei Day to my local kine friends and followers on Oahu–Hele mei hoohiwahiwa!) is special to me as a first-generation Serbian-American with more than a passing interest in my culture’s pre-Christian beliefs. The Friday before May 6, the fixed date of St. George’s Day, the traditional start of summer, has a lot of unique customs surrounding it that attest to very old and widespread pre-Christian beliefs preserved in rural as well as urban Serbian communities. This particular Friday that comes but once a year has a special name: Biljini Petak. The word Petak means “Friday” and biljini is an adjective related to wild herbs and flowering plants; hence, Biljini Petak can be best translated as “The Friday of Wild Herb-Gathering Before Saint George’s Day.” The fact that this year’s Biljini Petak falls squarely on Beltane pleases me greatly, as there is a lot of overlap between Serbian/Slavic and Celtic observances that clearly hail from a Pagan past.

By All Means, Do the Dew! And Gather Ye Herbs While Ye May

As with Serbian witchcraft, or vračara, in general, the activities surrounding Biljini Petak fall under the provenance of “women’s work.” What I find most moving about it is the mentoring involved: early in the morning, as my mother relayed to me, older women lead younger women and girls out of their villages and towns and into wild, uncultivated meadows and fields, their voices collectively ringing out in song. Their first agenda is to literally roll about in the morning dew, as well as dab some dew on their faces. This is considered to be an extremely important apotropaic gesture, one that ensures the prevention of sickness. It also helps ensure that women of child-bearing age will conceive without difficulty and have safe, uncomplicated births. Dabbing Bilijini Petak morning dew on one’s face is also a beauty enhancement.

The bulk of the women’s time together is spent identifying and harvesting specific medicinal plants, all of which would be used in the course of the year and which would have been taboo to harvest earlier in the spring (not unlike the Celtic taboo of bringing sacred hawthorn tree branches into the house prior to Beltane). My mother reports that she was encouraged to gather chamomile, mint, wild thyme, St. John’s wort, cowslip, rosehip, elder flower, yarrow, nettle, linden flowers and leaves, young willow branches, and a curious herb she only recalls by its folkname of kukureka–related, magically, to helping hens lay lots of eggs (the sound a clucking chicken makes is said, in Serbian, to sound like “kukureka”)–but which I have, with my father’s help, since been able to identify as hellebore. (As an aside, it was a huge taboo to bring kukureka anywhere near hens prior to Biljini Petak; they would have been cursed with the inability to lay eggs.) She also collected wild strawberries and was encouraged to stain her cheeks with their juice to create a natural blush. (Later in the year, she would go with her elders to harvest walnuts–aside from eating the nuts as a good protein source in the winter, she was taught, during the lean years of World War II, to boil the husks to make a shampoo out of it.)

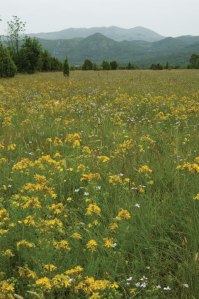

Wild St. John’s Wort growing in southern Serbia

Wild St. John’s Wort growing in southern SerbiaThe herbs, my mother insisted, were never cut, never lopped off. The entire plant was dug up with non-metal implements: sticks and their hands, basically. The plant in its entirety would be used medicinally as well as magically: flowers, leaves, stems, roots. Nothing would be wasted. And the songs were sung most enthusiastically at the time of the herb being disinterred, perhaps to thank it in advance for its life-giving properties, my mother surmised. But she certainly didn’t think about that at the time as a little girl; she just loved to sing, and she knew that she was a part of something special during those Biljini Petak outings with other girls, older female relatives, and the women of her town in the northern province of Vojvodina, near the Hungarian border, where she grew up.

Incidentally, plant diversity thrives in Serbia; in a 2010 report filed by the Republic of Serbia’s Ministry of the Environment (i.e., the Fourth National Report to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity), the data show that there are 4,000 indigenous species of plants, with more than 700 considered medicinal. Not bad for a country that’s roughly the size of the state of Wisconsin. Best of all, due to the history of what’s called “low input agricultural production,” especially in the mountainous (and thus less cultivated) southern part of the country, wild herbs are not affected by pesticides, heavy metals, fertilizers, or other harmful agents. It’s good to know that the magic/life force/ashe in these wild-growing herbs is as potent now as it was for my parents in the mid-twentieth century.

The typical Serbian farmer, the stock my father hails from, lives very much in a pre-Industrial age. There are no tractors, mowing machines, or hay balers. Hay is cut by hand with a scythe–by women as much as men–and piled neatly into conical haystacks.

The typical Serbian farmer, the stock my father hails from, lives very much in a pre-Industrial age. There are no tractors, mowing machines, or hay balers. Hay is cut by hand with a scythe–by women as much as men–and piled neatly into conical haystacks. “Give me wide open spaces”: Serbian farm country of Tornicka Bobija. Note the conical haystacks that are almost as large as the houses! 🙂

“Give me wide open spaces”: Serbian farm country of Tornicka Bobija. Note the conical haystacks that are almost as large as the houses! 🙂Welcome, Summer! The Magic of Đurđevdan, or Saint George’s Day: An Old Slavic God in a Threadbare Christian Cloak Comes A-Calling for Sheep’s Blood in Exchange for Fertile Fields and Good Times!

On May 6, known as Đurđevdan or the Feast Day of Saint George, the herbs that the women have gathered on Biljini Petak get “worked.” It’s the first day of summer and it’s all systems go! One of the first customs again involves a women’s-only outing, first thing in the morning, to the nearest flowing body of water: wreaths woven from flowers have to be ceremonially “drowned” to ensure that there will be adequate rainfall for the year’s crops. (Incidentally, according to the weather lore taught to my father, if it rains on the morning of St. George’s Day, the entire summer is going to be parched and pestilential.)

Multi-generational Cunning Women at work: the drowning of the wreaths on St. George’s Day morning, 2014. Photo courtesy of UNESCO

Multi-generational Cunning Women at work: the drowning of the wreaths on St. George’s Day morning, 2014. Photo courtesy of UNESCOA lot of the customs are apotropaic in nature, magically ensuring protection on the pastoral as well as the agricultural fronts; there’s much ado about livestock, and sheep take center stage on Đurđevdan–especially the sacred slaughter of lambs. According to my father, lambs were said to stop suckling their mothers’ milk at this time of year, and that was the cue that they could be killed by the head of the household for their meat as well as to ensure sreča, or good luck, for the home, the fields, and the herds for the remainder of the year. For example, my father recalls how, in his boyhood village of Gornji Milanovac in central Serbia, the strongest young men performed a great community service on St. George’s Day that was meant to ward off hailstorms: Carrying ashes, which would be strategically dispersed, the men would run clockwise around the village and the fields. When they arrived at the point at which they’d started, the finest young lamb would be donated by a farmer for slaughter. You guessed it: its blood was scattered on the periphery of the fields as well as marked on the walls of houses, not unlike what’s shown in this photo of Kosovo Albanian celebrations of St. George’s Day, 2006:

The village of Babaj Bokes, Kosovo. May 6, 2006. Photo courtesy of theguardian.com

The village of Babaj Bokes, Kosovo. May 6, 2006. Photo courtesy of theguardian.comMy father also reported that sometimes the ears were cut off the slaughtered lambs and placed in a local large anthill: This was a gesture meant to placate the forces of pestilence and prevent illnesses from striking the herds. He would also help his brother and father tie crosses out of hazelnut branches; these were hung up in barns and animal pens to provide an additional layer of magical protection for all livestock. Hung above the front door inside the house, such a cross would also protect against lightning and hail. This custom to me is very reminiscent of the Celtic one of tying rowan wood branches together with red thread to fashion similar apotropaic crosses.

Another custom involved the firing of shotguns over pens of livestock, or the wild areas where the livestock were free to roam and graze in the summer months. Upon firing their shells, the men would say, “As far as this gunshot goes, so too may all sickness and predatory animals be kept as far as possible from my animals.” To protect the animals against witchcraft (village witches did sling curses at each other, after all), wooden barrels were dismantled and the metal hoops were held up for small livestock to pass through, thereby invoking the apotropaic power of iron. Ashes from the wood-burning stoves and cauldron hearths were also scattered in circles around animals’ pens to keep the baleful magic of one’s enemies at bay.

A farmer milking his sheep in Dojkincima, Serbia, on St. George’s Day–the start of the milking season. Note the apotropaic flower wreaths on the animals’ necks.

A farmer milking his sheep in Dojkincima, Serbia, on St. George’s Day–the start of the milking season. Note the apotropaic flower wreaths on the animals’ necks.With the slaughter of the lambs not just for protection but to honor the Slavic god-turned-saint with communal feasting, Đurđevdan is known for being a festival of food. The winter religious taboos (in Eastern Orthodoxy) surrounding what types of foods can be eaten are broken; everyone is free to indulge in fresh meat and the fresh milk of cows and sheep, as well as the fruits of the season. For Serbian families that honor Saint George as their patrilineal protector–a unique-to-Serbs custom known as a slava, or Feast Day of One’s Ancestral Guardian–the feasting is even more elaborate, with the slavski kolač or saint’s bread specially baked and then ritually consecrated at morning Mass before shared in a large feast with one’s family members, neighbors, even total strangers!

A beautiful slavski kolač embossed with sacred symbols, baked for a St. George’s Day slava celebration. Note the decorative staple of the wildflower wreaths (in this case, chamomile).

A beautiful slavski kolač embossed with sacred symbols, baked for a St. George’s Day slava celebration. Note the decorative staple of the wildflower wreaths (in this case, chamomile).Once churchy obligations/ritual observances are out of the way, the day is devoted to having a good time outdoors, with much merry-making out in Nature. Not unlike Beltane customs, there is much dancing and leaping over bonfires. Young people court each other; established couples dash off into the woods and meadows for some frisky business. Everyone is bedecked in flowers. It’s an unhindered, all-out celebration of the life force, something that Serbia’s ethnic Roma (“gypsy”) community does very well:

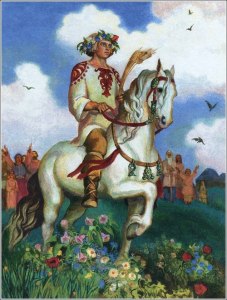

Outdoors or indoors, Đurđevdan is the ideal time of year to get some fancy footwork in with some kolo dancing: circle dances meant, when done clockwise, to honor the living (meant to honor the dead when danced counter-clockwise). The folk costumes’ elaborate details vary regionally in Serbia, especially when it comes to the symbolism in women’s embroidery, but the red-and-white hues worn by the men unequivocally inform us that we are in the presence of the life-giving, sun-kissed Slavic god Đurđev or Jarilo, who brings vegetation to life with each of His steps:

A beautiful troupe of Serbian kolo dancers

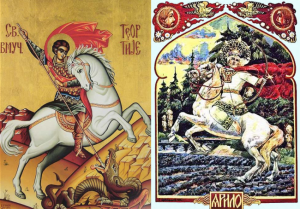

A beautiful troupe of Serbian kolo dancersWhether it’s because of the etymological connection of Their names (Đurđev and George) or the symbolism of the white, solar-associated horse and the defeat of the dragon (which, some scholars surmise, is tied to the serpentine or dragon-looking Slavic God of the Dead, Veles, with whom Đurđev engages in ritual combat and triumphs over), it’s not hard to see the connection between the Slavic god and the saint so widely venerated in Byzantine/Eastern Orthodox lands of the Balkans/southeast Europe and far northeastern Europe (St. George is Russia’s patron saint, for example):

Đurđevdan and the Magic of the Vile, or Fairy Women

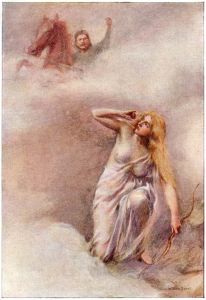

Whether Slavic God or Byzantine saint, Đurđev can be called upon to ensure protection against spiritual forces of dubious repute, especially the wild and formidable class of nature spirits known as the Vile (pronounced VEE-leh; this is the plural form–singular Vila) that one may encounter in the wild. These beings are especially active at this time of year, and they’re not entirely friendly towards humans (though, since they are thought of as heterosexual females, handsome mortal men are often singled out for sport). Depicted in Serbian oral epic poetry (especially the deeds of the King Arthur-like Kraljevic [Prince] Marko and his supernatural horse, Šarac) as indescribably beautiful women, arrayed in white, the Vile are fond of dancing and bathing in their lonely places in the wilderness. Like Valkyries, however, they’re also babes of battle, equipped with arrows that can kill with instant ferocity or cause someone to waste away from an inexplicable disease; it’s the Serbian equivalent of getting what the Anglo-Saxons called “elf-shot.”

The beautiful and haughty Queen of the Vile gets yelled at by Prince Marko, hero of Serbian oral epic poetry, for shooting her fairy arrows and mortally wounding a friend of his. Painting by English artist William Sewell for the 1914 publication of Hero Tales and Legends of the Serbians by Woislav M. Petrovitch.

The beautiful and haughty Queen of the Vile gets yelled at by Prince Marko, hero of Serbian oral epic poetry, for shooting her fairy arrows and mortally wounding a friend of his. Painting by English artist William Sewell for the 1914 publication of Hero Tales and Legends of the Serbians by Woislav M. Petrovitch.Incredibly, my father, to this day, swears that he saw a troupe of Vile dancing in a ring around a plum tree on the outskirts of his village on the morning of May 6, 1951, when he was eleven years old and he and his aunt were up first thing in the morning, headed to church for Saint George’s Day Mass. He describes the landscape as having been tinged by an Otherworldly mist, and that he was afraid as soon as he and his aunt set foot from her house. At first he said he couldn’t believe his eyes at what he saw–about nine or ten incredibly beautiful, mostly blonde, young women dressed all in white, slender and tall, their long hair unbound (a Serbian no-no back in those days, as women in public often had their heads modestly covered with scarves) and cascading well down their backs. They held hands and sang while dancing a kolo around a young plum tree that grew near a pond / wasn’t part of anyone’s orchard. My dad says his father’s sister urged him to look away and to make the Sign of the Cross and to spit on the ground in front of him. He obeyed her, and when he looked back at the plum tree the ghostly women had vanished…but they left behind a curious impression in the earth. Not just trampled grass, but the unmistakable stamp of their vračara, or witchcraft. My father says that nothing ever grew in that trodden ground ever again.

(My mother rolls her eyes and exclaims “Joj Bože!” or “Good God!” every time my father tells this story because she doesn’t believe him; it’s a cute thing to see, their different take on the matter. My mother is a retired civil engineer and she always searches for a rational explanation first. My father, though, is a magical man, a Son of Veles if ever there was one. I personally believe that my father saw what he claims he saw.)

Unless you have the clout of a Prince Marko to harangue the Vile into undoing their baleful magic aimed at you, it’s best to always have a little bit of garlic in your pocket when you go out into wild places. That, in addition to any iron implements (a horseshoe nail is unobtrusive and relatively small and portable), is the way to keep the Vile from targeting you with their arrows or luring you onto the wrong trails so you get lost.

But since everyone loves to dance and make merry on Đurđevdan, I think the best course of action should you come upon a troupe of dancing Vile is to join right in and show them your fancy kolo footwork!

Have a blessed and joy-filled Biljini Petak and Beltane weekend! And to my Serbian peeps who will honor Saint George next Wednesday by these time-honored rites, Srečna slava!

Reblogged this on Gangleri's Grove and commented:

A really interesting account of polytheistic practices in Serbia a generation ago. 🙂 Fascinating and inspiring read.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Galina! I’m glad this post resonated with you so!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is fascinating! Thanks so much for writing it!

LikeLike

I’m glad you liked it! My goal is to record as many of my family’s memories of these experiences of Serbian folk customs as possible, peel back the onion layers of Christian influence, and get to the throbbing Pagan heart at the center of these Mysteries!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this wonderful post!! I am also first generation Serbian -American and love peeling back those layers!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dobro nam došli, Natasha! Hvala i sve najbolje!

LikeLiked by 2 people

SO wonderful to meet a fellow Pagan Serb!!!!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s great to meet you too—drago mi je! For the longest time, I thought I was the only one. 😉 Živeli!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I have been thinking that for a LONG time too! 🙂 Ziveli!!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

You must write more about these Serbian customs, as they are fascinating! There is indeed a great similarity with the Gaelic/Celtic traditions. Keep it coming 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much, I definitely plan to! I am glad to hear your confirmation of parallels with Celtic traditions. And thank you for following my blog! Živeli! / Slainte! / Cheers! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tomorow is Đurđevdan. I want to say Srećna slava domaćine 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hvala i mir svima!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on amor et mortem and commented:

Today is Biljini Petak. Enjoy learning about the Serbian start of summer and the variety of customs that overlap with the Celtic Beltane. Srećan Biljini Dan! Have a Festive Day of Plant Medicine!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating stuff. There seem to be some similarities between the battle between Đurđev and Veles and Gwythyr and Gwyn on the 1st of May that seem to be fairly universal. It was interesting to hear about your dad’s experiences with the Vile and good to see these traditions living on in the kolo dancing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve often thought of my father as an avatar of Veles. 😉

LikeLike